Course Corrections — Part 2: Aligning Compass and Chart

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Sallying Forth

As I noted in Part 1 of this series, I have no sense of direction. Not a poor sense—none at all. Every direction I face feels—implacably—like North. If I’m heading south and need to orient myself on a paper map, I have to turn the map upside down so that it matches my direction of travel. (For anyone interested in the neuroscience behind this, I recommend “Dark and Magical Places” by Christopher K. Germer. On his 10-point scale, I’m a “1” and even that might be a stretch.)

This is all part of what I call my “spatial dyslexia”—a mismatch that turns 3D puzzles into cruel humiliations and cost me at least 10 points on my IQ test: I have no idea what shape a rotated object’s shadow will project when lit from above, one of the staple questions on standardized tests. (If you know the answer, please let me know in the comments!)

On the final, very long day of a backpacking trip, Vienna and I had a revelation: the cardinal directions on a boat—forward, aft, port, starboard—are fixed. “Left” and “right” change as your body turns, but directions on a vessel don’t. If I could use a map and compass to maintain a mental grasp on where true north lay and imagine myself aboard a boat perpetually pointing that way, perhaps I could orient to the actual terrain around me differently. For example, if we were walking south, I’d be facing aft on my magic north-pointing boat and so west would always lie to port. No more guessing at trail junctions.

Amazingly, it worked!

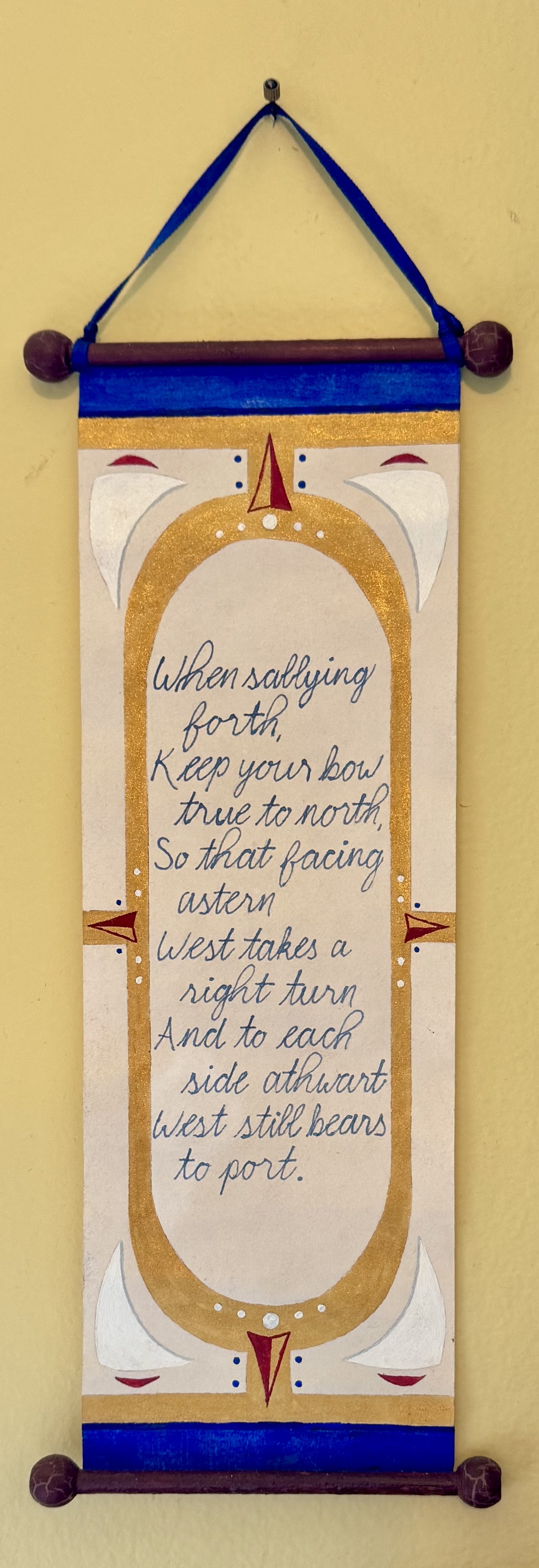

We spent many entertaining hours as we trudged back to the car refining a mnemonic to cement the concept and its application. Vienna eventually presented it to me as an illuminated calligraphic scroll (one of her many talents) for Christmas:

When sallying forth

Keep your bow true to north

So that facing astern

West takes a right turn

And to each side athwart

West still bears to port!

Astute readers will notice I’ve referenced both “map” and “compass” above. In my previous post, I drew an analogy between a magnetic compass and one’s moral compass. Both help us stay oriented—on trail, on water, or in life. But a compass isn’t enough. We also need a map—or, in nautical terms, a chart. And modern charts, like high functioning societies, require significant infrastructure and investment. Today, accurate maps and charts are constructed using satellites, immense amounts of data, inter-agency/governmental coordination, and authority across many institutions and stakeholders.

Today, I’d like to move from trail and sail to institutions and ethics in the broader world. Because ethical action at scale requires both personal virtue and institutional integrity. In other words, a compass and a chart.

I Have a Dream

I was a two-week-old embryo when I attended the March on Washington in late August 1963. I’m not sure if my mom even realized she was pregnant when she and my dad—both 23—joined the 250,000 demonstrators who marched on the National Mall for a day of peaceful protest, music, and speeches by political, cultural, and civil rights leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s soaring “I Have a Dream” speech.

In addition to Dr. King, most readers can probably name other heroes and milestones of the 1960s civil rights movement: Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Thurgood Marshall, John Lewis, “Bloody Sunday” on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, lunch counter sit-ins, Freedom Riders… But beyond the famous names and events lies the quieter heroism of tens of thousands of ordinary citizens who, year after year, often facing violence and unlikely odds, stood up for what they knew was right and insisted their voices be heard—and their votes counted.

The moral arc of the universe may indeed “be long,” to borrow Dr. King’s phrase (itself drawn from Unitarian minister Theodore Parker), but it only bends toward justice when people steer it that way. Moral formation is not a passive exercise.

One often-overlooked figure from the Civil Rights era is Dorothy Height. She led anti-lynching campaigns in the 1920s, served as the fourth president of the National Council of Negro Women, and helped organize the 1963 March on Washington. (Despite her leadership, she was not invited to speak—a reminder that inequity existed even within movements for equality.) Among her many quotable statements, one remains especially clear-eyed:

“I want to be remembered as someone who used herself and anything she could touch to work for justice and freedom… I want to be remembered as one who tried.”

Talk about a strong moral compass!

But collective action, however courageous, could only do so much. To endure, the civil rights movement had to be translated into institutional authority—a map or chart, to extend our metaphor. Landmark legislation like the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act. Judicial decisions like Brown v. Board of Education. Federal marshals escorting six-year-old Ruby Bridges to integrate her elementary school.

That dynamic—personal virtue generating collective norms, which then become institutional infrastructure—is central to how Vienna and I understand the mission of Leaving a Clean Wake. And yet it’s still an incomplete model. Laws and regulations only work if people uphold them. Institutions must enforce and maintain them. Anyone paying attention can see that many of the civil rights gains of the 1960s are now being steadily eroded—by individuals and institutions alike.

There is no “set it and forget it.” Moral formation, at both the personal and systemic level, is never one-and-done.

Plastics Redux

While essential to progress, personal virtue doesn’t always lead to new norms—it can be “hacked” or even weaponized by institutions acting in bad faith.

In my earlier post on the literal wake a boat leaves behind, I used the international MARPOL treaty to frame the different types of physical waste a vessel might discharge. Unsurprisingly, plastic is a major concern. But plastic pollution isn’t just a marine issue—it’s global. (Even extraterrestrial, if you count the growing halo of orbital debris.)

Problems of this scale require coordinated global solutions. In 2022, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) launched the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) on Plastic Pollution. Five international meetings later, no treaty has been finalized. Why? Because petrostates and the fossil fuel industry insist the problem lies not in plastic production, but in poor recycling and individual behavior. If only people were more responsible, they say, there would be no crisis.

Instead of a binding treaty with enforceable targets, countries like the U.S., Russia, and Saudi Arabia have pushed for a voluntary framework—one everyone knows won’t meaningfully address the rising tide of environmental and health impacts of the sea of plastic we are all swimming in.

That’s especially cynical given that viable alternatives to most consumer plastics already exist. These biodegradable, non-toxic materials have been developed outside the petrochemical industrial complex—but without support and investment to scale, they remain commercially disadvantaged.

Still, individual courage persists. Juliet Kabera, Rwanda’s lead negotiator, represents a coalition of 85 countries demanding a treaty with real teeth. “It is time we take [the threat] seriously and negotiate a treaty that is fit for purpose and not built to fail,” she said at INC-5 in South Korea—earning a standing ovation. Kabera also warned: “Plastic production is on track to triple by 2050, but today’s levels already are unsustainable and far exceed our recycling and waste management capacities.”

Kabera is both speaking truth to power and working within institutional frameworks to enact change. So far, she and the countries she represents seem to be swimming upstream.

Blaming individuals for systemic harm is a familiar playbook. The tobacco industry ran it for decades. The fossil fuel industry still uses it to deflect responsibility for the climate crisis. The food industry pins the obesity epidemic on individual failures of will rather than the food they’ve engineered to be addictive. When institutions dodge accountability by invoking personal virtue—while knowingly sabotaging the very systems that would enable ethical action—they’re not misinformed. They’re gaslighting.

In Part 1, I recounted how our family nearly ran our boat aground despite having a true compass—because the chart was wrong. In that case, the error seemed to stem from bureaucratic neglect, not malice. But when institutions deliberately distort the chart while blaming the navigator, the ethical valence is very different. That’s not neglect. That’s betrayal. And it leads all of us toward the rocks.

Virtue at Scale

If the Civil Rights movement showed how moral courage can transform institutions—and the Plastics Treaty negotiations showed how institutions can weaponize individual virtue to avoid accountability —these next examples offer something else entirely: ethical systems that emerged organically—built from shared values, community norms, and individual conviction without relying on government intervention. We’ll look at each in turn: first science, then open-source software.

The scientific method is the product of centuries of development—from Copernicus and Galileo to Darwin and Einstein, continuing into the present day. Every major element of modern science—peer review, reproducible results, double-blind placebo-controlled trials, institutional review boards—emerged from within the scientific community and is largely policed by it.

A signature achievement of this transparency and self-discipline was the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines in the early months of the pandemic.

Like many institutions, science now faces challenges from AI authorship, dis- and misinformation, and funding distorted by the politics of the moment—but as an international, self-organizing edifice, I remain hopeful about its future integrity. Its infrastructure, while imperfect, remains resilient in its ongoing quest to pursue facts—and just the facts—wherever they lead.

Born in universities and enthusiast communities (and later embraced by corporations), the open-source software movement shares a similar spirit. Movement founders believed software source code should be freely accessible and collaboratively developed. As the initiative gained steam, that belief was translated into real infrastructure—public code repositories, transparent licensing models, peer review mechanisms, and community standards.

The result? Linux, Git, Python, strong cryptography, and even Wikipedia. Today, many of the systems we rely on most—including parts of the internet itself—run on open-source software. And we’re now seeing the emergence of “open-weight” AI models, which allow smaller labs and independent researchers to build applications and innovate without needing corporate-scale resources. (We’ll save a discussion of the dangers and benefits of AI for future posts.)

These examples offer a different kind of moral arc—one rooted not in protest, but in participation. Their compass is internal. Their chart is collaboratively drawn. But the crucial virtuous relationship still holds.

Ecumenism

“The Kingdom of God is not a matter of getting individuals to heaven, but of transforming the life on earth into the harmony of heaven.”

As we said at the outset of Leaving a Clean Wake, our aim is to be as ecumenical as possible in honoring different worldviews and to focus instead on our shared humanity. In other words: not to preach.

In that same spirit of humanist ecumenism, I’d like to close this already long post with a final example of moral formation at the societal level that, in fact, comes from preachers. It too follows the dynamic we’ve been exploring—between personal virtue and institutional responsibility—but it comes from a more explicitly religious crucible: the Social Gospel.

The Social Gospel movement emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the United States and Canada as a response to the harsh realities of industrialization, poverty, and inequality. Its leaders—theologians like Walter Rauschenbusch and others—believed that Christian ethics should not be confined to personal salvation, but must be applied to public life: labor rights, urban reform, education, health, and justice.

The movement held that sin could be embedded in social structures, not just in individuals. It argued that a moral society required both compassionate people and just institutions. Churches became centers of advocacy for labor laws, child welfare, and housing reform—blending faith with activism.

The same moral sensibility that animated the Social Gospel found new expression in later social movements: the environmental movement catalyzed by Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” which sought to embed ecological responsibility into public consciousness and policy; the labor movement, which continued to push for safer working conditions and equitable pay; and the movement for marriage equality, which expanded the circle of belonging and civil protection.

And while it had lost momentum by the mid-20th century, the Social Gospel profoundly influenced the Civil Rights movement, with leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. drawing deeply from its legacy.

These examples all reflect the same interplay of personal conviction and structural reform. Each reminds us that the long moral arc of the universe doesn’t bend towards justice on its own. Rather, it bends when people, and the systems they shape, pull together with purpose.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Over several posts, Vienna and I have been quietly building toward a broader vision of Leaving a Clean Wake—one that goes beyond evocative metaphor into the realm of ethical framework.

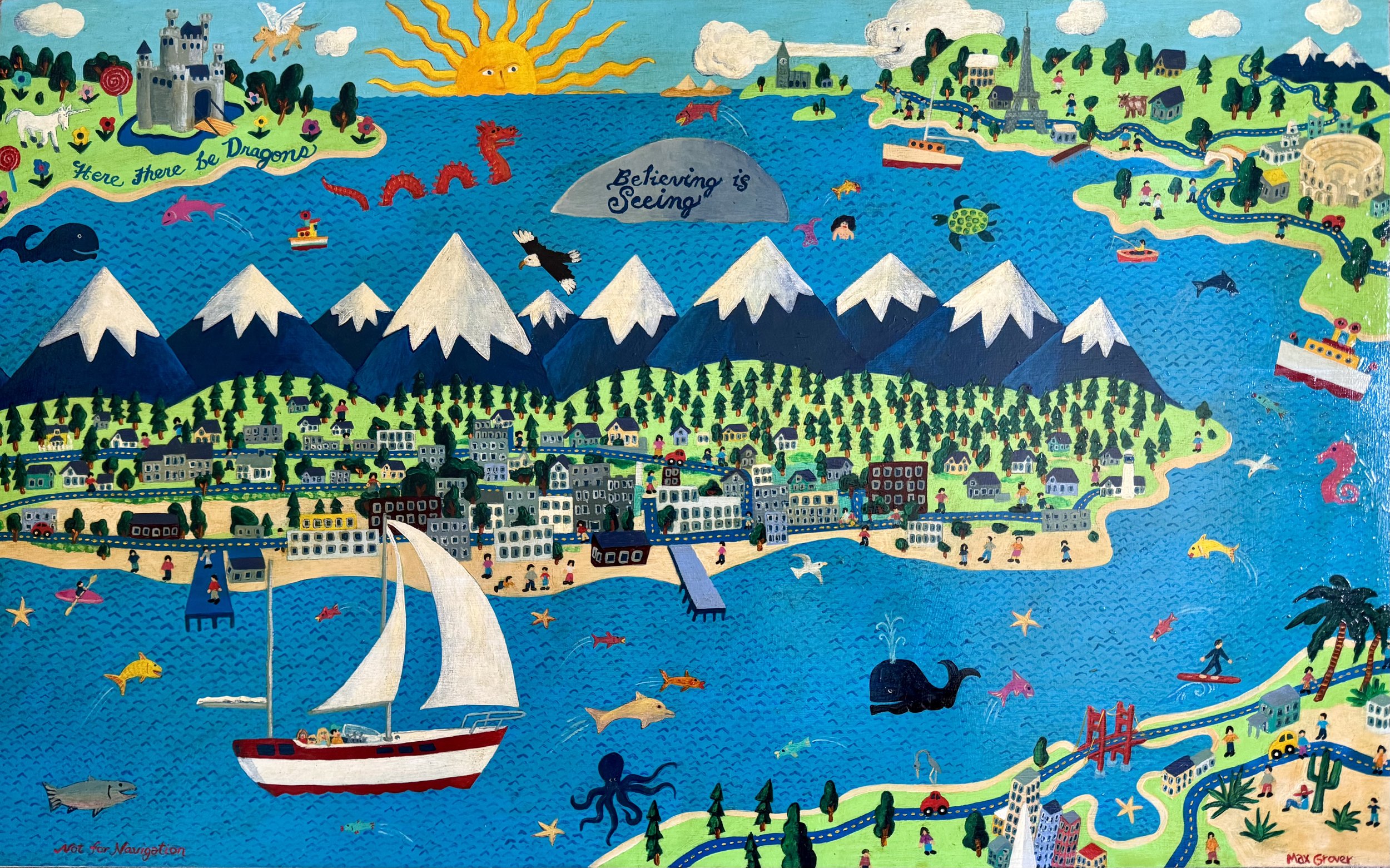

In Part One of our introductory series, we explored what a boat’s wake actually is, how the bluewater cruiser’s maxim to leave a clean wake reminds us that we leave traces behind whether we intend to or not, and how that insight can shape a way of living—one grounded in intention and aligned with our values.

In my post examining the literal wake a boat leaves behind, I introduced the idea that personal virtue is necessary but not sufficient. Ethical action at scale also requires institutional authority: the kind provided by governments, legislation, regulations, and other collective infrastructure.

Vienna’s post comparing Leaving a Clean Wake to other guiding principles—Leave No Trace, The Golden Rule, and others—helped us clarify that LACW is not just a container for existing ethics. It’s a first-principles framework capable of generating entirely new insights. Like a software API, it can function independently to derive ethical behavior from context. (For example: someone unfamiliar with Leave No Trace, but committed to Leaving a Clean Wake, could reason their way to packing out their trash in the backcountry.)

Then, in Part 1 of this Course Corrections series, I introduced the metaphor of the compass and the chart. If personal virtue is the compass, institutional infrastructure is the chart—and ethical navigation requires both.

In this current post, I’ve tried to show how those two forces—individual virtue and institutional accountability—interact dynamically. At their best, they create a virtuous cycle: intentional action at the personal level scales up to norms, which shape institutions, which in turn codify those values through laws, regulations, and enforcement.

But infrastructure isn’t enough on its own. Regulations only work if people uphold them. And when institutions fail—whether through corruption, neglect, or bad faith—the burden often shifts unfairly onto individuals. Even hard-won social gains can erode if not continually defended. As we’ve said before, the relationship between individuals and institutions is co-dependent, and always evolving. Yet when both are aligned with the ethic of Leaving a Clean Wake, they can form a feedback loop that nudges the moral arc of the universe just a little more toward justice.

Vienna and I are not professional philosophers—but we are committed practitioners of this idea. We would love to hear your reactions to the more expansive version of Leaving a Clean Wake we’ve been laying out. Please share your thoughts in the comments.

And don’t worry—we’ll lighten the tone in the next few posts. You can expect more side-by-side comparisons with other ethical frameworks, profiles of people and organizations who embody clean wake principles, and practical encouragement for how each of us can navigate our lives with a little more awareness, grace, and care.